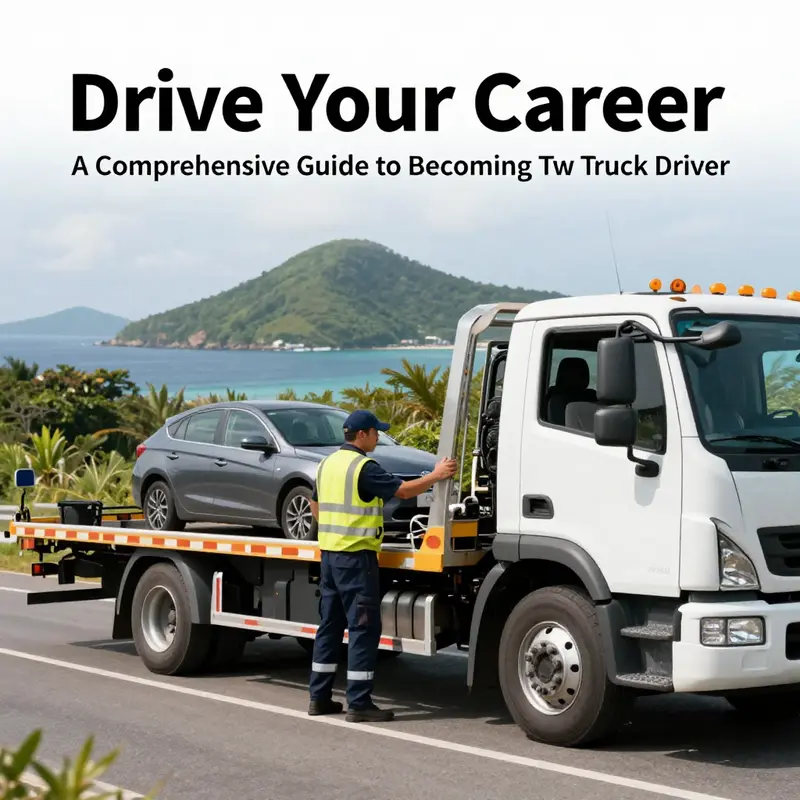

In the vibrant world of roadside assistance and vehicle recovery, tow truck drivers stand as vital lifelines to our communities, especially in island locales. As local auto repair shops, car dealerships, property managers, resort operators, and commercial fleet operators often need towing services, understanding the pathway to becoming a tow truck driver is paramount. This guide outlines the necessary steps, age and licensing requirements, and the specialized training needed to excel in this crucial role. Each chapter will unfold vital information, from meeting age and licensing prerequisites to mastering communication skills required for effective service delivery.

From Age to Authority: Mapping the Path to a Tow Truck Driver Career

In a field where every highway shoulder could become a temporary workplace, becoming a tow truck driver is less about swagger and more about navigating a structured ladder of age limits, licensing, and regulatory compliance. The route is not identical in every state or country, but the logic holds: you prove you can handle a heavy vehicle, you prove you can handle the job responsibly, and you prove you can stay on the right side of the law while you help stranded motorists. The following passage unpacks the core milestones in a way that helps you plan a practical, legal, and safe ascent into this essential service.

Age acts as the first gate. In the United States, the raw baseline is usually 18, but the scope of what you can do at that age depends on the jurisdiction and the kind of towing you’ll perform. Some operations require you to be 21 or older, especially when you’re communicating on interstate roadways or carrying larger payloads. Others may permit younger drivers for non-commercial duties, but if you want to pull a heavy tow truck or operate across state lines, you’ll want to plan around the higher age thresholds. A practical mindset is to think of 18 as the entry point to begin the process, with many operators preferring or requiring 21 as the moment you gain broader maneuverability, broader assignments, and access to a wider range of insurer contracts. Age, then, is less a personal preference and more a regulatory lane you must enter with patience and clarity about your local rules.

With age acknowledged, the next essential step is securing a valid driver’s license. A standard state-issued license forms the foundation. Your goal is to demonstrate a clean driving history and an ability to comply consistently with traffic laws, as any flag in your record can echo into the CDL stage. The license itself is a signal to employers that you are capable of basic road operation; it is the passport that allows you to even begin the more specialized, higher-stakes training required for commercial work. In many cases, an employer will look at your license history alongside your communication skills and reliability. Tow work demands punctuality, attention to customers, and the discipline to follow procedures even when time is tight on a roadside scene. The leap from a standard license to a commercial one is where the real regulatory test begins.

The Commercial Driver’s License, or CDL, marks the bridge from ordinary driving into commercial operations. In most contexts, towing a trailer-equipped vehicle places you in the CDL category, typically Class B. If your operation involves a heavy trailer or a configuration beyond standard single-vehicle towing, some jurisdictions may require you to pursue a Class A CDL, which covers more comprehensive heavy vehicle operations. In a few places, there are special endorsements that tailor your license to towing tasks. The path to CDL begins with a careful application and the recognition that you are entering a field where safety testing, medical clearance, and precise knowledge of vehicle control are non-negotiable. The application process commonly requires a written knowledge exam to verify your understanding of road rules and commercial vehicle regulations, followed by a skills test that demonstrates your ability to operate the tow truck, including backing, turning, securing loads, and performing basic recoveries. The medical examination is a constant companion to CDL eligibility, ensuring you meet the physical demands of seeing, hearing, and moving in ways that keep everyone on the road safe. No list of steps would be complete without acknowledging the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration’s role in setting and enforcing these standards. The CDL program is designed not just to test you once, but to ensure ongoing compliance through periodic medical examinations and continued licensure requirements.

Beyond the basic tests, there is often a layer of specialized training that employers or vocational programs administer. This training dives into the kinds of equipment you’ll encounter, such as winches and hydraulic lifts, and it emphasizes the practicalities of working around high-speed traffic, responding to accidents, and handling different kinds of vehicle damage. You will learn how to assess scenes, secure a vehicle without causing further harm, and protect yourself and others on the roadway. You’ll also be taught the legal responsibilities that accompany tow operations. The best programs connect technical skill with situational awareness, a blend that keeps you prepared for weather, poor lighting, and the unpredictable rhythm of roadside assistance. Even with formal training, the job remains demanding in real-world conditions; it tests your judgment, your steadiness under pressure, and your ability to communicate clearly with dispatchers, customers, and law enforcement when a scene can become tense.

Maintaining a successful path in tow work requires a clean driving record and reliable personal conduct. Employers value drivers who demonstrate responsibility both behind the wheel and in customer interactions. Standards on record cleanliness may vary, but the general expectation is a history free from major incidents that could increase risk on the road or at a recovery site. The ability to adhere to safety protocols, wear appropriate PPE, and follow lawful traffic management practices is a daily requirement. In addition to a physical record, a driver must have functional English proficiency that supports reading traffic signs, understanding orders from dispatch, and communicating with customers and authorities. This language component is essential to ensure that guidance is understood, which in turn reduces the chance of missteps during critical roadside operations. If you are pursuing this career from abroad or as a non-citizen, you’ll also need to secure the appropriate work authorization. Legal status matters because it governs your eligibility to operate commercially and to enter into contracts with employers, insurers, and clients who rely on your service.

The actual career path often unfolds through a combination of formal credentials and on-the-job learning. Some aspiring tow operators begin by apprenticing under experienced professionals, absorbing procedural habits, safety routines, and the nuances of different equipment. In other words, the badge of a licensed tow driver is earned as much through practical trust as through paper credentials. Once you’ve earned the necessary licenses, endorsements if applicable, and a confirmed medical clearance, you become eligible to apply to towing companies, roadside assistance fleets, and related service providers. From there, the job market typically rewards those who demonstrate reliability, a calm demeanor, and a willingness to take ownership of challenging scenes. Many drivers find it most effective to start with a single employer, learn the local corridors, and gradually expand into a broader range of services as they gain experience and reputational capital. The progression rarely happens in abrupt leaps; it comes through consistent performance, consistent safety records, and a network of recommendations from supervisors and colleagues who know you can manage complex recoveries with care.

What that means in practical terms is a plan you implement step by step. Begin with confirming the minimum age and licensing requirements in your state or country, then map out the exact path to obtaining your CDL, including the endorsements and the medical standards you must meet. Check with your local DMV or equivalent transportation authority for the most current specifications, and be prepared to undergo the medical evaluation required to secure your medical examiner’s certificate. Simultaneously, seek out reputable training opportunities—whether through a vocational program, an accredited driving school, or an employer’s internal program—that emphasize hands-on practice with towing equipment, safety procedures, and legal responsibilities on highways. Keep your driving record clean by avoiding DUIs or reckless behavior and by addressing any incidents with transparency and corrective action if they occur. If you are navigating this path from outside the United States or a jurisdiction with different rules, remember that the exact age thresholds, licensing classes, and endorsements will differ; treat the process as a layered, jurisdiction-specific journey rather than a single universal formula.

As you prepare to take the formal steps, you may find it helpful to engage with broader resources that provide practical context—stories from the field, common pitfalls, and a sense of what daily life on the tow truck feels like. For readers who want a grounded perspective beyond the statute books, several practitioners share experiences on industry blogs and professional forums; you can gain a sense of how the day’s assignments arrive, how teams coordinate at the scene, and how operators balance speed with safety. A good way to connect with that practical voice is to explore the Island Tow Truck blog, which offers insights and real-world perspectives from people moving through this exact licensing and training journey. For readers who prefer a more technical emphasis or downstream safety strategies in fleet operations, there are related discussions on emergency response and fleet preparedness that reinforce the seriousness and the responsibilities of this line of work. The point is not to rush the process but to cultivate the habits of safety, accountability, and ongoing readiness that define professional towing.

Finally, the licensing track you pursue should align with your long-term goals. If you aim to work on your own or to manage a smaller operation someday, your early training should emphasize not only the mechanics of tow equipment but also the fundamentals of customer service, incident reporting, and insurance concepts. Building a solid foundation now pays dividends later, because the licensing landscape is not static. Changes in state rules, evolving safety standards, and new equipment technologies all shape the competencies a driver must demonstrate. This is a field where continued education pays off over time, not merely at the moment you pass a single test. And because the roadways themselves are imperfect, the ability to stay calm, think clearly, and follow a disciplined protocol makes the difference between a scene that ends safely and one that escalates.

To summarize, becoming a tow truck driver in a regulated environment is a staged process built on age thresholds, licensing steps, medical clearances, and hands-on training. It requires a practical understanding that your initial license is just the doorway and that the real work begins once you transition into commercial operation, maintain a clean record, and master the language and safety expectations that guide every roadside assignment. As you navigate this path, use each milestone not as a gate meant to restrict you but as a checkpoint that confirms you are ready to perform a complex, high-stakes service with professionalism. For ongoing guidance, you can consult the broader resources in your region, and, when you want to see how these steps translate to day-to-day experience, explore the Island Tow Truck blog for practical context. External resources and official guidelines provide the formal backbone to your path: FMCSA guidelines.

Navigating CDL Requirements for Tow Truck Drivers: A Practical Roadmap to Getting Behind the Wheel

To operate a tow truck in the United States, you must understand the gatekeeping rules that keep roads safe and orderly. The Commercial Driver’s License (CDL) is the primary credential for most heavy-duty towing operations, and its specifics are shaped by federal standards set by the FMCSA and by state implementations. The core idea is that heavier vehicles and more complex configurations require higher license classes and more stringent testing. This chapter outlines how to map a job description to the appropriate CDL class, endorsements, and training, and how to prepare for the knowledge and skills tests, the practical driving requirements, and the day-to-day realities of roadside work. It also highlights safety, legal, and professional standards essential to a successful tow-truck career. Optional reading: related industry posts on CDL readiness, endorsements such as the “T” endorsement, and how transmission choices can affect licensing restrictions. The path forward is straightforward: identify the vehicle and duties, choose the right CDL class and endorsements, complete the required testing and training, maintain a clean driving record, and pursue hands-on experience through apprenticeship or employer-provided programs. Remember to check your state’s specific rules, because endorsement scope and testing requirements can vary. External resource: https://www.dot.gov/

Gatekeepers to the Road: Mastering the Examination Process to Become a Tow Truck Driver

The examination process to become a tow truck driver acts as a practical gatekeeper, separating aspiring operators from those who will handle heavy vehicles on crowded highways. It is not merely about passing a test; it is about proving readiness to work in environments where split-second decisions protect lives, other motorists, and the broken down vehicle you are assisting. While the details can shift by state and country, the core purpose remains consistent: verify that you possess the knowledge, skills, and health to perform tow duties safely, responsibly, and legally. For many candidates, this journey begins with basic eligibility. In most jurisdictions, there is an age floor and a CDL requirement that ensures you can manage a commercial vehicle with the weight and complexity a tow truck represents. You will likely need to be old enough to hold a commercial license and to demonstrate the maturity expected of someone who can operate under high-pressure conditions. The CDL itself is not a mere formality; it is the formal recognition that you can control a large, maneuverable vehicle while adhering to traffic laws, weather conditions, and the unpredictable dynamics of roadside work. The Class B endorsement is commonly associated with tow truck operations, reflecting the need to drive substantial commercial vehicles. In some cases, depending on the weight of a trailer or the nature of the tow apparatus, additional endorsements or license classes may come into play. The pathway is designed to be rigorous not to deter, but to ensure safety and reliability in the field. The examination itself combines theory and practice in a way that mirrors the real responsibilities you will shoulder on the job. The written component tests your grasp of road rules, vehicle inspection standards, and specific safety procedures that govern towing operations. This is not trivia; it is the framework that supports sound judgment when you are faced with a flat tire at midnight, hazardous traffic, or a damaged vehicle that must be recovered without causing further harm. The knowledge part also covers the legal responsibilities that come with roadside assistance, including how to document incidents, communicate with dispatch and law enforcement, and protect yourself and the customer from liability. The skills test looks different but is equally essential. It assesses your competence in vehicle inspection, control of the tow truck, and on-road maneuvers that reflect the realities of a road-side recovery. You will be asked to demonstrate a thorough pre-trip inspection, where every system is checked for signs of wear, leaks, or malfunction. You will show you can operate controls smoothly, perform precise steering, and execute safe backing and turning under constrained conditions. You will be tested on how you secure loads, attach tow equipment, and manage recovery gear such as winches or hydraulic lifts. These tasks are not abstract; they are the practical routines you will rely on when a vehicle is in a compromised state and other drivers are relying on you to maintain order and safety. As you progress toward the exam, you should expect to encounter background checks and drug screening as standard prerequisites. These checks are designed to confirm that your record and your conduct align with the professional standards of the industry. A clean driving history contributes to a trustworthy profile that many employers seek, and it often correlates with the ongoing ability to secure steady work. The requirement for drug screening underscores the safety-sensitive nature of operating heavy machinery on public roadways. A positive result or an incomplete screening can derail an application before you reach the actual road test. The physical examination is another cornerstone of the process. The body must be able to endure long hours, sudden shifts in workload, and physically demanding tasks that may arise during a tow. Medical standards help ensure that fatigue, vision, hearing, and general health do not compromise safety. This is why people who pursue tow truck driving ally themselves with a regimen of regular checkups and transparent health reporting. Some employers supplement licensing with additional training programs focused squarely on towing operations. These programs may emphasize emergency response tactics, safe towing practices, and the correct handling of equipment specific to a tow truck—like winches, hydraulic lifts, and recovery gear. Hands-on practice in a controlled setting helps you translate classroom knowledge into dependable field performance. It also prepares you for the unpredictable realities of roadside assistance, from dealing with sudden weather changes to managing different vehicle types and damage scenarios. In many states, the path to official licensing and endorsement is a matter of aligning your readiness with the jurisdiction’s requirements. You will want to consult the state DMV or the equivalent transportation authority to confirm the exact steps, forms, fees, and testing windows. Keeping an organized record of your driving history, medical assessments, and training certificates can streamline the process and prevent delays. The arc of this journey is not simply about ticking boxes; it is about earning the credibility that comes with demonstrated competence. A successful candidate approaches the examination as a holistic evaluation of capability, temperament, and accountability. It is not enough to pass; you must be consistently reliable in the field, capable of exercising good judgment when faced with limited visibility, high speeds, or dynamic roadside hazards. As you study for the written portion, you can frame your preparation around the fundamental questions that reappear across testing regimes. What does a proper pre-trip inspection look like on a tow truck? How do you identify a potential safety risk before the vehicle leaves the depot? What are the correct procedures for attaching a vehicle to a tow unit and securing it for transport? These questions anchor the exam in practical reasoning rather than memorized answers. When you take the skills test, the examiners are watching not only your technique but your decision-making under pressure. They want to see you communicate clearly with dispatch, fellow responders, and customers. They want to observe your situational awareness and your ability to maintain control while carrying out complex tasks such as lane changes with a loaded trailer or negotiating tight spaces in a crowded lot. The emphasis on load security cannot be overstated. In tow operations, unsecured or poorly secured loads can shift unexpectedly, posing risks to drivers, pedestrians, and neighboring vehicles. Demonstrating mastery in securing, transporting, and warning others about potential hazards is as important as knowing how to engage a winch or how to position the tow truck for a safe recovery. The examination process also intersects with ongoing professional development. Many employers encourage or require follow-up training after licensing, to keep pace with evolving safety standards, new equipment, and updated regulations. This approach acknowledges that safety is not a one-time credential but a discipline maintained through practice, reflection, and continuous learning. A thoughtful applicant will view the exam as the gateway to a career rather than a mere hurdle. They will supplement formal testing with practical experience—perhaps by working as an apprentice or shadowing seasoned operators—to gain exposure to real-world scenarios and the rhythm of roadside work. Even with strong test results, ongoing compliance remains essential. A clean driving record, adherence to safety protocols, and timely updates to medical and certification statuses are ongoing requirements for licensed tow truck drivers. The journey through examinations and licensing is, in essence, a journey through professional integrity. It requires discipline, situational judgment, and a commitment to the highest standards of public service. For those who want to keep a finger on the pulse of industry learning and safety culture, there is value in integrating broader resources and community knowledge. The The Island Tow Truck blog provides a steady influx of insights into safety practices, drills, and real-world reflections from the trade. Engaging with that resource can help you translate exam-ready knowledge into practical, day-to-day competence. The Island Tow Truck blog can be a helpful companion as you prepare, not a substitute for the formal licensing process. As you integrate studying with hands-on practice, remember that the exam is designed to protect you, your colleagues, and the people you will assist on the road. It judges readiness in a structured, transparent way, and it creates a standard that makes tow drivers dependable allies in a world of sudden breakdowns and demands. The path to certification is deliberate and doable when you approach it with a plan, a calm mind, and a willingness to learn from both successes and missteps. In the larger arc of preparing for a tow truck career, the exam is the moment when knowledge becomes action, and policy becomes practice on the highway. External resources can provide additional perspectives on licensing pathways, such as the guidance outlined in this external reference: https://www.chinaautonews.com/2025/07/31/how-to-upgrade-to-a2-license/.

Forging Competence on the Road: Specialized Training for the Modern Tow Truck Driver

Becoming a tow truck driver starts long before the first call comes in. It unfolds through a structured, specialized training path that translates classroom rules into practiced, reliable responses under pressure. This training sits at the crossroads of mechanical understanding, precise hands-on skill, and the calm discipline needed to manage risk in ever-changing roadside scenes. Across reputable programs, aspiring operators move through a common arc: mastery of heavy‑duty equipment, extensive hands-on recovery practice, and certifications that confirm readiness to perform at high levels of safety and accountability. While a general driver’s license opens the road, specialized training closes the gap between a permit to drive and a capability to recover, secure, and move vehicles safely, ethically, and efficiently. It is this distinction that turns a hopeful applicant into a dependable professional whose decisions can spare people harm and save valuable assets on busy highways and rural corridors alike. The best training programs recognize that tow work is as much about judgment and care as it is about technique, and they design curricula to cultivate both, so graduates carry confidence into every scene they encounter. This is where the journey toward mastery becomes tangible, practical, and portable across different employers and jurisdictions.

Heavy‑duty knowledge begins with the machines themselves. Trainees learn to operate a spectrum of equipment—rotator tow trucks capable of dynamic pivots, car carriers designed to cradle frames securely, and a range of integrated booms, winches, and control systems that convert a stubborn lift into a controlled maneuver. Instruction goes beyond locating levers and switches; it builds an understanding of capacities, hydraulics, electrical interlocks, and the subtle differences between hoisting a compact sedan and stabilizing a heavier, irregularly shaped load. In many programs, students study load path, friction, and leverage, so they can predict how a given rig will respond as forces shift, wheels roll, or tires meet a rough surface. The aim is to create operators who can anticipate movement, choose the correct rigging approach, and execute lifts with precision, reducing the risk to crew members, motorists, and bystanders alike. Rigging is taught as both art and science: which points to anchor, how to distribute tension, and when to switch from one method to another as a scene evolves. Trainees practice a repertoire of techniques—frame‑secure joints, wheel lifts, anchor points, and auxiliary supports—so they can adapt quickly without compromising stability.

Hands‑on experience is the backbone of effective training. The most successful programs weave practical recovery scenarios into each module, moving learners from controlled environments to more stressful, real‑world contexts. Trainees perform stabilizations, set up multi‑point restraints, and execute controlled pulls while monitoring for movement or collapse. They drill complex recoveries involving overturned vehicles, vehicles on slopes, and recoveries in low‑visibility conditions, such as night or rain. The emphasis is on precision and pace: how to place equipment without collision, how to communicate clearly with teammates, and how to adjust plans in response to new information from the scene. Instructors stress that a scene is never a single gift-winished lift; it is a sequence of small, deliberate steps that, taken in order, keep everybody safe. The most robust curricula also integrate scenario planning and decision‑making drills that force students to balance speed with caution, a balance that often determines whether a call ends with a safe resolution or a costly outcome.

Safety and legal responsibility form an equally critical strand. Operators must be fluent in the rules that govern roadside work, traffic control, and the chain of custody for evidence and insurance processes. The training environment flags the hazards that accompany a roadside response—the proximity of fast‑moving vehicles, unpredictable weather, uneven ground, and damaged fuel or fluids. Students learn to position rescue and recovery equipment to shield workers, motorists, and bystanders, while maintaining access routes for emergency responders. They study proper PPE use, high‑visibility protocols, and safe distances from lanes of travel, as well as the legal implications of each action taken at the scene. In addition, communication is framed as a safety tool: dispatchers, law enforcement, and insurance adjusters rely on clear, precise information about location, scene conditions, and actions being taken. As the training progresses, students internalize a disciplined approach to risk assessment, ensuring that every decision is justified by safety standards and documented procedures rather than expediency.

Certification and standardization are the bridges between training rooms and the job sites. Many employers seek candidates who have earned formal certification acknowledging competence in heavy‑duty recovery, while some jurisdictions require state endorsements that accompany the CDL. Even where requirements vary, programs that emphasize a recognized standard tend to produce operators who can move smoothly between employers and regions. A thorough training framework will cover pre‑planning, rigging, stabilization, lift operations, and post‑recovery procedures, with a strong emphasis on hazard awareness and incident documentation. The National Association of Certified Automotive Professionals (NACAP) provides a detailed guide that outlines curriculum standards and safety protocols used by modern training programs. The NACAP framework helps programs align with industry expectations, ensuring that graduates possess a consistent baseline of competencies for high‑capacity recoveries and hazardous scene conditions. This alignment matters not only for day‑to‑day reliability but also for professional mobility as regulations evolve and fleets expand across jurisdictions.

Even with formal credentials in hand, the road to true expertise is incremental and ongoing. Many drivers begin as apprentices, learning from experienced operators who bring scene‑by‑scene wisdom—the unspoken know‑how that cannot be fully captured in manuals. Apprentices observe, assist, and gradually assume greater responsibility, building a repertoire of practical skills and situational judgment. The apprenticeship path often includes inside‑the‑cab simulations, heavy‑rigging practice, and progressively independent recoveries under close supervision. As confidence grows, the operator may tackle more demanding calls: complex multi‑vehicle recoveries, fleet‑side assistance for commercial accounts, or high‑risk incidents on busy interstates. Each step reinforces professional judgment, accountability, and adherence to safety protocols. Importantly, this progression is not a race; it is a careful cultivation of craft, the steady accumulation of hours, and the steady refinement of decision‑making under pressure.

The training ecosystem is designed to be dynamic, reflecting changes in equipment, laws, and industry expectations. Prospective drivers should seek programs that offer real‑world simulations, exposure to a range of gear, and opportunities to perform under varied weather and traffic conditions. A robust program will also provide access to mentoring from seasoned operators, opportunities to observe different styles of handling torque and momentum, and structured pathways to recertification as technologies and standards evolve. Because emergencies rarely arrive neatly labeled as “training scenarios,” genuine preparedness means building flexibility into the skill set—so that when a call comes, the driver can adapt the plan without sacrificing control or safety. For those who want to explore practical applications and field-tested strategies beyond formal coursework, industry blogs and learning communities can be a valuable sounding board. A representative resource for ongoing, real‑world insights is the entry found in industry discussions on essential fleet emergency response strategies. You can read more here: Essential Fleet Emergency Response Strategies.

Finally, a well‑structured training plan should not end with certification alone. It should establish a trajectory that incentivizes continual improvement: refreshing knowledge to keep pace with new stabilization methods, updating rigging techniques as equipment evolves, and maintaining a record of practice lifts and successful recoveries that demonstrate growth. Training is most effective when it becomes a habit—an ongoing commitment to safety, accuracy, and professionalism. In time, apprentices become qualified operators whose calm, methodical approach under pressure earns the trust of customers, colleagues, and the communities they serve. This is the threshold where a person moves from simply knowing how to drive a tow truck to knowing how to steward a scene from first call to final resolution. As you plot your path, remember that the strongest preparation combines rigorous coursework, hands‑on proficiency, and a culture of safety that remains constant no matter the job or the conditions. For additional guidance on standards and certification, see the NACAP Training Certification resource: NACAP Training Certification.

Standards on the Road: Mastering Safety, Communication, and Professionalism as a Tow Truck Operator

Tow work sits at the intersection of logistics, compassion, and quick, precise action. As you move from trainee to professional, the standards you uphold become as important as the mechanical skill you bring to a recovery. Roadside emergencies demand calm, competent judgment, and a consistent code of conduct that protects you, your crew, and the people you serve. The shift from classroom to curbside is not merely about knowing how to hook a strap or operate a winch; it is about translating training into daily discipline that keeps everyone on the road safer and restores normalcy as quickly and safely as possible. In this sense, professional standards are the framework within which every tow, every call, and every interaction takes place. They shape how you inspect your vehicle, how you move through traffic, how you manage a scene, and how you communicate with drivers who may be stressed or frightened. Those standards are the quiet backbone of the job, the unglamorous but indispensable work that makes you reliable in hours of uncertainty and pressure.

The first breath of any shift should feel like a check on a quiet stream: a pre-trip inspection that covers more than a cursory glance. You walk around the tow truck with a purpose, looking for the small deviations that signal trouble—uneven brakes, lights that flicker at the turn of a switch, a winch that doesn’t wind smoothly, or hydraulic components that show signs of wear. This isn’t a ritual to fill time; it’s a risk-reduction system. When you verify every system is functioning before you even roll onto the road, you reduce the chance of a failure that could escalate a fragile situation into a roadside crisis. The road does not forgive laxity, and a thorough pre-trip check becomes the habit that keeps you in control when conditions are less than ideal. The confidence you gain from that predictability translates into steadier handling of the vehicle you pull, the load you secure, and the space you need to maneuver from curb to highway shoulder.

Handling a disabled vehicle on public roadways is another arena where your training must translate into precise technique and mindful restraint. You learn the latitude and the limits of your equipment and your plan. Proper vehicle handling means understanding how to navigate tight spaces, how to position the tow truck to protect other road users, and how to support a damaged car without exacerbating its injuries or creating additional hazard. It means knowing when to use wheel chocks, when to deploy recovery equipment, and how to choreograph the sequence of hooking, loading, and towing so that each step reinforces safety rather than creating new risk. It also means selecting the right approach for the specific scenario—whether you’re dealing with a vehicle that won’t roll, one with leaking fluids, or a car that needs to be stabilized before it can travel. In practice, this is not a single skill but a continual process of assessment and adjustment, a discipline that turns complex scenes into organized operations.

Alongside technical proficiency, a comprehensive understanding of traffic laws and on-road responsibilities is essential. The road is a shared space, and your actions influence the flow of traffic and the safety of everyone nearby. You must know how to position yourself so you can control the scene without creating new hazards. This includes the correct use of warning lights and safety signage, proper lane placement, and respectful interaction with other drivers who may be anxious or impatient. Clear visibility of the operation, predictable movements, and adherence to lawful procedures all contribute to a safer environment for both you and the people you assist. There is a line between urgency and recklessness, and professional drivers walk that line with measured speed and deliberate, lawful actions.

The heart of professional performance, however, lives in how you communicate. Tow truck work is as much about people as it is about machines. A driver’s ability to speak with clients, to listen, and to convey information calmly can de-escalate situations that start with fear, frustration, or anger. When a motorist pulls over and looks to you for help, your tone matters more than your entitlement to a fast recovery. Clear, respectful, and empathetic communication helps customers feel heard, reduces tension, and paves the way for cooperative problem-solving. Active listening is not passive; it is a deliberate practice of confirming you understand what the driver is experiencing and what outcomes matter most to them. In many cases, the person you are helping just wants to know what is happening next. Your responses should acknowledge concerns, outline the immediate steps you will take, and set realistic expectations about timing and outcomes.

Equally important is the professional language you bring to every dispatch, every radio call, and every field report. Documentation is the invisible thread that stitches together accurate service records, accountability, and efficiency. A reliable tow operator keeps detailed notes on vehicle conditions, locations, and client interactions. This practice supports not only the current operation but future safety reviews, insurance considerations, and performance assessments. In day-to-day terms, that means taking time to capture precise facts, such as the vehicle’s make and model, visible damage, fuel status, and any fluid leaks. A well-kept log becomes a reference point for your team and for managers who rely on your records to coordinate multi-vehicle recoveries or to file accurate claims. The habit extends to digital dispatch systems and standardized radio codes, which ensure that every team member understands and can act on the information in a consistent way. This consistency reduces miscommunications, speeds up response times, and builds trust with clients who see you as a reliable, professional partner rather than a last-minute helper.

As you advance in your career, you realize that professional standards are a living, evolving set of practices. They grow from the discipline you cultivated during training and are reinforced by ongoing training, feedback, and a culture that values safety above speed. Employers increasingly expect riders of the tow truck line to be proficient in both technical and interpersonal aspects. For instance, many operations now formalize training in the use of winches, hydraulic lifts, and recovery equipment within safety parameters. They also emphasize understanding legal responsibilities when working on highways, deliberate methods for handling different vehicle types, and the capacity to adapt to emergencies with poise. In this environment, staying current with best practices and regulatory guidelines becomes part of your professional identity. It is not an optional add-on but a core component of career longevity and service quality.

One practical pathway to sustaining this standard is to integrate high-quality resources into your daily routine. For example, industry guidance can point you toward structured approaches to emergency response that improve coordination with other responders and reduce risk on the scene. Referring to practical templates and strategies—such as those highlighted in the broader field of fleet emergency readiness—helps you calibrate your own practice to industry benchmarks. A focused resource like the essential fleet emergency response strategies page can offer concrete illustrations of how teams coordinate during multi-vehicle incidents and how you, as an operator, fit into that broader system. This kind of integration matters because it translates into faster, safer outcomes on the road. You can explore practical examples and programmatic insights at essential fleet emergency response strategies.

Safety, communication, and professionalism do not exist in a vacuum. They are reinforced by a culture of accountability that recognizes the consequences of every decision made behind the wheel. The path to becoming a tow driver who embodies these standards begins with the basics you learned in training and extends into every shift you work. It includes a conscientious approach to pre-trip checks, a careful method for parking and approaching scenes, an up-to-date understanding of traffic laws, and a commitment to speaking with clients in ways that acknowledge their vulnerability while steering the process toward resolution. It means documenting with accuracy and clarity, so colleagues and supervisors can trust the narrative of a day’s work. Over time, these practices cohere into a professional demeanor that other drivers and customers come to rely on. In a field where fear and irritation can escalate quickly, the consistent application of safety protocols, thoughtful communication, and disciplined record-keeping becomes the signature of a responsible tow operator.

For those who are building a career in this field, the payoff is not only in safer operations but in the trust you cultivate with clients and the reputation you earn within your company and the broader roadside assistance community. The path is cumulative: the early emphasis on safety evolves into leadership in on-scene coordination, mentoring newer drivers, and contributing to a culture that values meticulousness and kindness alike. Finally, the standard you set for yourself today creates the foundation for continued learning, adaptation, and professional growth tomorrow. As you prepare to add the tow truck driver role to your professional toolkit, remember that mastery is not a single skill but a disciplined way of approaching every moment on the road. For broader safety guidance and authoritative guidelines, you can consult the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration at https://www.nhtsa.gov.

Final thoughts

Becoming a tow truck driver is not just a job; it’s an integral part of local community support, ensuring vehicles are safely assisted and moved in times of need. By understanding the age and licensing requirements, grasping the CDL processes, navigating through the examination stages, embracing specialized training, and maintaining professional standards, aspiring tow truck drivers can build fulfilling careers rich in community impact. With each of these aspects integrated, you can step into the role ready to serve with confidence and skill.