For local auto repair shops, car dealerships, and resort operators, understanding how many vehicles a tow truck can effectively and safely tow is crucial. Various factors such as the size of the tow truck, the weight and size of the vehicles being towed, road conditions, legal stipulations, and specialized transport vehicles all play a significant role in determining towing capacity. This article delves into these factors across five comprehensive chapters, ensuring you equip yourself with the knowledge to make informed decisions in your towing operations.

null

null

Tow Limits and Weight Rules: How Vehicle Size Dictates How Many Trucks a Tow Truck Can Move

The simple, consumer-facing question—how many trucks can a tow truck tow?—tends to invite a neat, numeric answer. In the real world, there isn’t one. The capacity of a tow truck to move more than one vehicle hinges on a web of factors that start with the machine’s design and end with the road under its wheels. To understand why the number can range from one to a handful, it helps to move through the logic of the operation as a single, continuous narrative rather than a checklist of discrete categories. The first truth is that tow trucks are built for recovery, not for wholesale convoy operations. A standard roadside recovery unit, whether it uses a flatbed, a wheel-lift, or a traditional wrecker arm, is engineered to recover and transport one disabled or damaged vehicle at a time. Even when the machinery appears imposing, the fundamental loading geometry and control systems are optimized for single-vehicle handling. A typical setup involves anchors, lines, and clamps calibrated to secure that one vehicle securely for transport, with the chassis and towing mechanism tuned to distribute forces in a controlled, predictable way. The storage space, braking leverage, and steering dynamics have all been optimized for one vehicle. This is not a hard natural law carved in stone, but a design and safety compromise that makes sense in most roadside contexts where precision and predictability matter most. When a tow operator is called to a scene with a single broken or immobilized vehicle, the process remains straightforward: secure the vehicle, confirm weight limits, connect the appropriate transport method, and execute a measured lift and load that preserves the integrity of both the tow truck and the towed vehicle. The operator relies on the rig’s rating, the vehicle’s weight, and the road environment to determine whether a second vehicle can be accommodated in the same operation without compromising safety or control. Even in a fleet with high-capacity rigs, the default practice is to move one vehicle per operation. The reason for this conservative stance has to do with physics as well as risk management. A vehicle towed behind a truck imposes vertical, horizontal, and rotational loads on the rig. Add a second vehicle, and those load paths multiply in complexity. Every connection point, every tie-down, and every braking reaction must be managed in real time, with the potential for sudden shifts that could destabilize the tow. The margin for error narrows quickly when more weight or more mass is being controlled from a single point of attachment. Consequently, even a substantial 20-ton wrecker, which may feature a rotating boom and dual winch system designed for precision recoveries, remains, in practical terms, a one-vehicle operation in most scenarios. The same logic that governs a precision recovery also governs the way the system distributes weight through the hitch, the boom, and the chassis. When a heavier vehicle is involved, the operator may be forced to modify the approach—reconfiguring the rig, choosing a flatter, more stable surface, or using alternate winching sequences to keep the load within safe angles. The organization and training behind a tow crew are built around these core principles: never exceed rated capacities, always maintain control of the load path, and keep critical systems reduntant and secure. Specialized heavy-duty tow trucks complicate the calculation, but they also illustrate the limits of the one-vehicle rule without discarding it. In certain operations, particularly during large-scale evacuations or controlled body-to-vehicle movements in a closed setting, teams may use multiple smaller carriers in a coordinated convoy. In such cases, the planning and execution demand exacting attention to total mass, staggered accelerations, braking profiles, and road conditions. The practical takeaway is that while it is theoretically possible under rare and highly controlled conditions for several smaller vehicles to be towed in a single plan, this is not standard roadside practice. The emphasis remains on managing weight and maintaining a secure, stable load. Weight is the most immediate constraint. The greater the mass of the towed vehicle, the greater the force demands on the towing assembly, brake systems, and hydraulic components. A large SUV, a cargo van, or a heavy pickup can quickly push a system near its safe operating envelope, reducing the number of vehicles that can be towed safely in a single maneuver. When the weight of the target vehicles approaches or exceeds the rated capacity of the rig, operators must reduce the load, not the safety margin. The towing system is engineered to handle margins, not to endure reckless experimentation. Road conditions are the second decisive factor. On smooth urban streets, with good lighting and minimal grade, a conservative operator may feel more confident testing the edges of a rig’s capabilities. In practice, even in favorable conditions, the control systems and attention required suffice to keep the operation to one vehicle. On rough terrain, steep grades, or in adverse weather, the margin is slashed again. Slippery surfaces, unstable shoulders, or blind curves generate a need for even more conservative load management. The goal remains constant: prevent damage to the towed vehicle, protect the tow crew, and avoid creating a scenario that could result in loss of control. Legal and safety regulations underpin these decisions. Manufacturer specifications define the upper limits and safe operating practices, and local regulations often impose additional constraints on load distribution, ramp angles, and escort requirements. Compliance with these rules is non-negotiable. Operators are trained to evaluate each situation against a strict checklist: weight, center of gravity, hitch integrity, winch load, brake load, and the effect of any auxiliary equipment such as dollies or additional stabilizers. The broader implication for fleet planning and emergency response is that the number of vehicles a tow truck can move in a given operation is not a fixed figure but a function of context. In everyday practice, a standard tow truck will focus on one vehicle per operation. In larger, well-coordinated scenarios, multiple small vehicles may be managed in a single, carefully orchestrated plan, but this requires a level of planning, coordination, and road management that goes far beyond ordinary roadside recovery. It is precisely this nuance that makes the topic so important for fleet operators and responders who must protect life, property, and the integrity of the equipment they rely on. For teams responsible for island fleets, port contingencies, or multi-vehicle incident response, the question often shifts from “how many can we tow at once?” to “how do we structure an operation that keeps every vehicle and every crew member safe while meeting mission goals?” In this context, the discipline of planning becomes essential. A well-prepared operation will couple the one-vehicle rule with flexible, scenario-specific strategies. It may involve staging vehicles in a controlled sequence, using multiple rigs, or leveraging specialized transport configurations that are suited to small, light cars while preserving the safety margins required for heavier ones. The synergy between design limits, driver training, and operational protocols creates a dependable framework for decision-making when confronted with the unpredictable environments tow work always encounters. Acknowledging the limits also opens space for thoughtful, proactive preparedness. Where possible, fleets can map typical weight profiles for vehicles commonly encountered in their region and align that data with upstream decision points in dispatch software and on-scene checklists. In practice, this translates to more accurate load planning, safer lift strategies, and better protection for the equipment—while still enabling responsive, efficient service during emergencies or breakdowns. For readers seeking deeper technical grounding, a broader technical overview of tow truck specifications and their applications offers additional context on how manufacturers design capacity into different classes of trucks and why those design choices matter in real-world operations. Essential fleet emergency response strategies can provide practical framing for how agencies balance speed, safety, and throughput in multi-vehicle scenarios. As this chapter has outlined, though, the core principle remains simple and consistent: safety and control trump any urge to stretch the limits. In the end, while it might be theoretically possible for a specially configured operation to move more than one vehicle under rare conditions, standard practice centers on moving a single vehicle at a time. The most important factor is always the equipment’s rating, the vehicle’s weight, and the road and environmental conditions that apply at the moment of recovery. For operators and researchers alike, this anchoring truth guides both day-to-day decisions and longer-term planning. External factors and future innovations may broaden the envelope—new stabilization technologies, better distributed load systems, or smarter weight-tracking tools—but the foundational caution remains: the safest, most reliable choice is to treat a tow as a one-vehicle operation unless a highly controlled, carefully engineered plan proves otherwise. External readers can explore more about the technical landscape of tow trucks and their capabilities through targeted industry resources that discuss specifications and applications in depth, which helps frame why the one-vehicle norm endures in most contexts. For comprehensive background, consult established technical overviews such as the detailed analysis provided by industry guides on tow truck specifications and applications: https://www.towtruckguide.com/technical-overview-best-tow-trucks-specifications-applications. This chapter’s synthesis aligns with that broader engineering perspective and reinforces the central message: weight, size, and safety govern everything in tow operations, and those constraints define how many trucks a tow truck can effectively move in practice.

Tow Truck Capacity in Real Conditions: How Road Surface, Vehicle Weight, and Strategy Shape What a Tow Truck Can Move

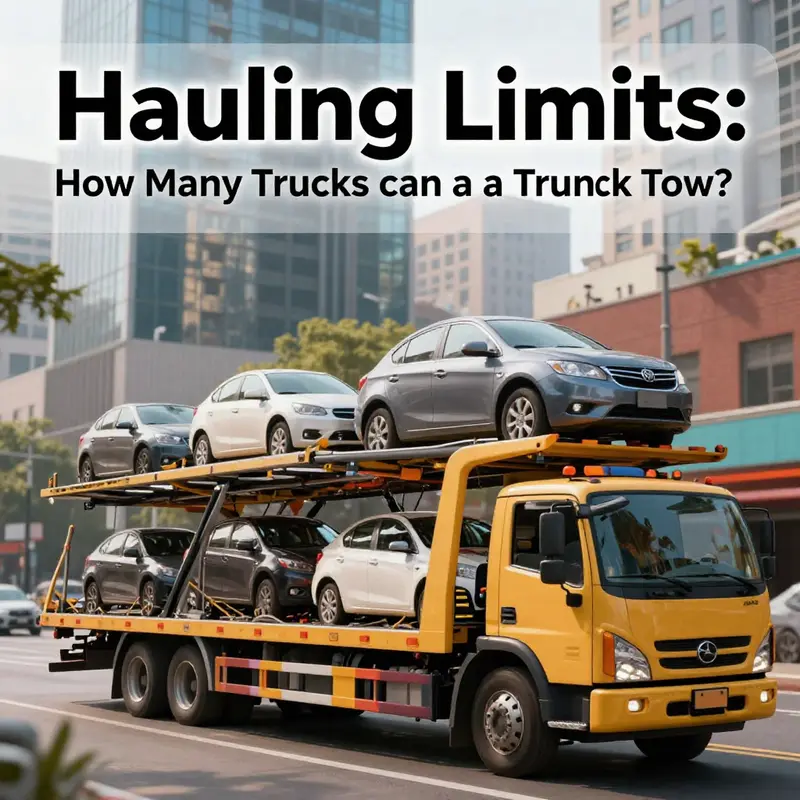

When people ask how many trucks a tow truck can tow, the instinct is to expect a clean, fixed answer. But the honest truth is more practical than poetic: capacity is a function of the vehicle, the vehicle being towed, and the surface beneath the tires. The overall topic—how many trucks can a tow truck tow—is less about a universal number and more about a careful balance among equipment limits, weight distribution, and the realities of the road. In everyday roadside work, the most reliable guides are the specifications printed by manufacturers, the constraints of the road, and the professional judgment built from experience. The conversation begins with the type of tow truck. Small, pickup-based tow trucks exist to move a single vehicle at a time, and their design priorities emphasize quick recoveries, maneuverability, and safety margins for light-weight tows. Their engines, frames, and winching gear are engineered to handle one standard passenger car, not a string of vehicles chained end to end. Operationally, attempting to tow multiple cars with such a machine would push the limits of its ballast, braking stability, and hitch configuration, risking damage to the towed cars, the tow truck, and innocent bystanders. The next tier expands capacity. Medium tow trucks, often built on two-axle frames, bring greater power and a larger overall weight rating. These machines can typically tow two or three standard passenger cars if each vehicle remains within the payload and distribution allowed by the truck’s limits. The math, in practical terms, is about weight per vehicle and how it is spread across axles, tow points, and the braking system. The more mass there is, the tighter the allowable margin becomes for both acceleration and deceleration, especially on public roads where braking demands and steering stability are critical. When a vehicle’s weight approaches the upper limit, even a seemingly small miscalculation—like a slight shift in center of gravity or an unexpected gust of wind at highway speeds—can prompt a dangerous scenario. Consequently, most operators keep topeaks conservative and plan for the load to remain within a tested safety envelope. At the high end of standard roadside recovery, large tow trucks with three axles and enhanced braking capacity are designed to haul four to six standard passenger vehicles, again depending on the weight and size of each towed vehicle and the truck’s own gross vehicle weight rating. Even here, the capacity is not a simple sum; it is a constraint that factors in wheel lift or drive-line configurations, tire load, and the stress placed on the towing bar, winches, and stabilizers during the recovery process. In very rare circumstances, and only with specialized, heavy-duty equipment designed for multi-vehicle moves, some operations may approach or exceed the four-to-six window when the towed vehicles are unusually light or nearly empty. But those cases are exceptions rather than the rule, and they require meticulous planning, careful staging, and a clear, risk-aware objective that prioritizes safety over speed. The landscape is further complicated by the flatbed, or rollback, style of tow. Flatbeds are prized for minimizing vehicle damage during transport, because the entire vehicle can be loaded onto a level platform. This method often allows for safer recovery on uneven terrain and through challenging weather, since the vehicle isn’t being dragged or lifted by the wheels alone. Yet even flatbeds typically tow just one vehicle at a time in a roadside setting. Their stability comes from the design intention: secure, controlled loading rather than the simultaneous movement of multiple units. This is an important distinction, because the instinct to maximize throughput must yield to the physics of balance, friction, and the structural limits of the equipment. The underlying rules governing capacity remain consistent: the vehicle’s weight and size, the tow truck’s own rating, and the road conditions all conspire to determine how much can be moved safely. The size and weight of the target vehicle are pivotal. A large SUV or a heavy van can dramatically reduce the number of pulled units, often limiting the operation to a single vehicle even when the tow truck has substantial nominal capacity. In contrast, smaller, lighter vehicles can allow a truck to manage two or three, provided the combined weight does not exceed the manufacturer’s specifications and the load is distributed in a way that preserves traction and steering control. Road conditions further sharpen the brakes on any multi-vehicle plan. Smooth, dry roads in good repair permit operators to operate closer to the maximum rated capacity, but even then the margin is narrow. Wet or icy surfaces reduce traction; rough pavement introduces unexpected jerks in load dynamics; poor visibility demands slower speeds and more conservative maneuvering. All these factors reduce the safe number of vehicles to tow, and they amplify the risk of a skid, a tow rope or chain failure, or a misaligned load. A crucial distinction emerges when discussing specialized transport vehicles versus standard roadside tow rigs. Long-distance, industrial, or multi-vehicle transport solutions exist and are capable of moving more vehicles in a single operation. These are not typical roadside rescue tools; they include dedicated auto transporters or multi-car trailers designed for secure, long-haul moves. They can carry eight to twelve small cars under ideal conditions, but their design and operation require different infrastructure, driver training, and regulatory compliance than the average tow truck. Even with such specialized equipment, the prevailing rule remains: safety and proper load distribution trump the urge to maximize the number of vehicles moved at once. The practical takeaway is a straightforward one. In ordinary roadside practice, the number of towed vehicles is usually one, sometimes two or three under carefully controlled circumstances and with vehicles of compatible weight. If a recovery scenario involves multiple cars or unusual weight combinations, the operator must reevaluate the plan, potentially staging the mission into separate moves to maintain safety at every step. This careful approach aligns with the broader imperative of regulatory compliance and professional judgment. The manufacturer’s specifications, the vehicle’s weight, the road surface, and the environment all set non-negotiable boundaries. And while industry standards exist to guide practice, local rules and the specifics of a given incident will shape the final decision. For fleet managers and operators who want to optimize preparedness without compromising safety, a point of reference is found in the broader strategies that organizations adopt to handle emergencies. The right approach blends equipment selection with clear risk assessment, crew training, and a well-rehearsed response plan. For those seeking practical guidance on coordinating fleets during emergencies, the topic expands into a broader conversation about resilience and readiness. See the resource on essential-fleet-emergency-response-strategies for a detailed framework that can inform field decisions and operational protocols in a range of scenarios, including multi-vehicle recoveries when conditions permit. The link serves as a consolidation of best practices, illustrating how a thoughtful plan supports safe outcomes rather than hasty attempts at moving more units than the terrain will allow. Of course, any real-world application must reference official safety standards and guidelines. These standards emphasize that every operation must respect the towing equipment’s limits, the vehicle’s weight, and the prevailing road conditions. Where the science of towing meets the art of judgment, outcomes improve through disciplined practice, thorough inspection, and conservative decision-making. For readers who want to verify high-level safety guidance, official standards and guidelines from respected authorities in this domain are readily accessible online, such as the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. In sum, the question of how many trucks a tow truck can tow dissolves into a sober calculus: the capacity is not a fixed figure but a careful balance. One vehicle is the default, with two or three possible only when weight, balance, and surface allow. When the load grows too large or the surface grows too treacherous, the prudent choice is a staged, single-vehicle approach that prioritizes control and safety over throughput. The road rarely cares for the math, but professional operators do, and their training teaches the same essential lesson: safety is the framework within which all decisions about capacity are made. For further reading on how fleets plan for emergencies and balance multiple service demands, consider the strategic outline linked above, and for a broader perspective on regulatory expectations and safety benchmarks, consult the official highway safety resources available to the public.

Tow Limits in Focus: Legal, Safety, and Real-World Realities of How Many Trucks a Tow Truck Can Move

The question of how many trucks a tow truck can pull is not a riddle with a single answer. It is a field of practice defined by engineering, regulation, and the unpredictable variables of an on‑scene maneuver. The simplest truth is this: a tow truck’s capacity to move another vehicle is determined by its rated towing capacity, a specification issued by the manufacturer and printed in the manual or on the vehicle data plate. That rating reflects the design limits of the chassis, the strength of the hitch or mounting system, axle loads, braking capacity, and the overall balance of the tow setup. When people ask how many trucks can be towed at once, they are really asking about what a specific machine can safely and legally handle under the conditions at hand. Because tow trucks come in a spectrum—from compact light-tow units to heavy-duty, multi-axle recovery vehicles—the answer varies with the machine, the target vehicle’s mass, and the road on which the operation occurs. In practice, a standard tow truck is designed to tow only one vehicle at a time, particularly when the towed vehicle is a passenger car or light truck. Even when a second vehicle can be hauled in certain configurations, the limits imposed by the manufacturer, the weight distribution, and the safety margins usually keep a single-tow operation as the default. This is not merely a matter of capability but of controlled, predictable handling on public roads. The moment one adds a second towed vehicle, everything changes: the braking distance lengthens, the steering response grows heavier, and the risk of axle or hitch overstress increases. The data from manufacturers and safety authorities consistently supports the principle that multi-vehicle towing is rare and reserved for specialized equipment, very specific circumstances, and carefully controlled environments. The practical implication of this is clear to most operators who daily weigh the economics of a scene against the physics of load and the law. The smallest, most ubiquitous category of tow truck is typically a pickup-based unit or a light-duty carrier. These machines are often sufficient to move a single compact car or another small vehicle, provided the total weight remains within the configured limit. They are not built to handle a convoy of cars, and attempting to do so would push the vehicle beyond what the rig was designed to manage, compromising safety and violating the spirit of the manufacturer’s guidelines. Moving up the ladder to medium-duty tow trucks—two-axle configurations and similar designs—changes the calculus. These machines inherit greater power, more robust suspensions, and more substantial frames. They can tow two or three standard passenger vehicles in theory, assuming the towed vehicles stay within the combined weight threshold and the load is evenly distributed. Even here, the conditions matter. A slight miscalculation in weight distribution, an uneven surface, or a sudden shift in momentum can overwhelm the system. In other words, capability does not exist in a vacuum; it is a relationship among the machine, the load, and the environment. The largest standard roadside recovery units—three-axle or heavy-duty configurations—offer a noticeably higher towing ceiling. In ideal circumstances, and with a carefully planned setup and the appropriate attachment arrangements, these machines might haul four, five, or even six standard cars. But this is rarely the daily norm. It is more of an exceptional capability that is deployed only when the situation demands it and when all regulatory and safety checks are met. And there is a different class altogether: specialized transport vehicles. Long-distance haulers and professional auto transporters, designed for multi-vehicle conveyance and long hauls, can carry eight to twelve small cars on dedicated trailers. Yet these are not roadside rescue vehicles and require distinct licensing, equipment, and logistics. They are powerful, but their use is governed by separate standards and permissions. Across all these categories, the central, unwavering constraint is safety. The road surface, weather, traffic density, and the condition of the vehicles involved all play decisive roles. In rough terrain, on steep grades, or amid rain, snow, or ice, the maximum permissible load shrinks. The operator’s situational awareness—knowing when to reduce load, adjust speed, and deploy braking strategies—becomes as important as the mechanical limits on the tow rig. The legal framework mirrors this practical caution. Local regulations, weight limits, permissible configurations, and licensing requirements all dictate what is allowed on a given road or highway segment. Exceeding the gross vehicle weight rating (GVWR) or violating axle load limits can trigger fines, license consequences, or more severe outcomes if control is compromised. When fleets need to manage multiple vehicles in one operation—think fleet recoveries after a major incident or disaster response—they often require special permits and use multi-trailer configurations that are specifically approved by transportation authorities. Such operations are the exception, not the rule, and they demand trained personnel, specialized equipment, and meticulous compliance with rules designed to prevent loss of control or brake failure under the added weight. In a serious academic take on coordinated vehicle movement, a 2024 study in an engineering-focused journal examined how advanced tow systems can operate under controlled conditions. Even in such high-tech contexts, the conclusion remains clear: only one vehicle is to be towed at a time, unless the operation is explicitly configured, permitted, and supervised for multi-vehicle movement. This is a stark reminder that the allure of power and capacity must never override the safeguards built into the system. The discipline here is practical and protective: never assume more than your rig is rated for, and always verify the combination of truck, load, and route against the manufacturer’s specifications and local laws. For readers seeking practical guidance in real-world settings, the most reliable rule of thumb is to check the tow truck’s owner’s manual and the vehicle’s specification plate. These sources provide the official numbers that govern safe operation. In addition, consult the local department of motor vehicles or equivalent authority to understand the regulatory landscape your team must navigate. It is also wise to remember that even with a robust understanding of capacity, the plan must be flexible. A calm, pre‑planned assessment of the scene, a stepwise loading strategy, and a continuous monitoring of dynamics—brake responses, hitch stability, and tire conditions—are essential. Integrating these checks into a smooth workflow means that the tow operation remains predictable, even when the environment is anything but. For teams looking to translate theory into practice in the field, there is value in linking the guidance to broader fleet-readiness resources. To explore how emergency-response strategies can integrate with towing operations, consider visiting resources such as essential-fleet-emergency-response-strategies. This kind of strategic framework helps ensure that a tow team can respond quickly while staying squarely within safety and regulatory boundaries. At the same time, operators should maintain a clear awareness of manufacturer guidance and local laws. In the United States, for example, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) lays out the safety standards governing towing practices, emphasizing that improper towing can increase stopping distance, reduce maneuverability, and damage componentry. These considerations are not abstract; they translate into real consequences on busy roads and at accident scenes. The overarching bottom line is simple and consistent across jurisdictions: a standard tow truck should never tow more than one vehicle at a time unless explicitly authorized and equipped for such tasks. This is not a limitation designed to restrict capability but a prudent rule intended to safeguard drivers, towed vehicles, bystanders, and the public at large. The road to safe towing is paved with diligence: understanding the specific machine’s rating, respecting weight and axle limits, planning for the terrain and weather, obtaining the necessary permits for high-load operations, and adhering to established safety standards. For those seeking a longer view on how these practices fit into overall fleet resilience and safety culture, the broader literature on emergency-response readiness and vehicle recovery highlights the same principle: do only what you can do safely, and expand capacity only when the system as a whole supports it. External resources such as official safety portals provide the authoritative guidelines that keep this principle in check. External resource: https://www.nhtsa.gov

Tow, One at a Time: The Real Capacity of Tow Trucks in Everyday and Extreme Recoveries

When people ask how many trucks a tow truck can tow, they are often chasing a simple numeric answer. The reality is more nuanced. Tow trucks are specialized machines designed to recover and transport a single disabled or damaged vehicle with the best balance of safety, control, and efficiency. The idea of a tow truck as a multi-vehicle hauler springs from two places: a misunderstanding of the word tow in general terms, and a few dramatic media moments that hint at large-scale recoveries. In everyday roadside operations, however, the norm is clear and conservative: one vehicle at a time. This single-vehicle focus is what keeps salvage crews within the safety envelopes defined by the equipment’s limits, the environment, and the legal framework that governs roadside recovery and transport. The emphasis on one-tow-at-a-time is not merely a convention; it is a design principle embedded in the construction of flatbeds, wreckers with booms, and slide-in models. Each type plays to a core strength—securement, stability, and predictable handling—so that the towed vehicle remains intact, and the operator maintains precise control through the recovery sequence from curbside to repair bay or storage facility.

To appreciate why one is the prevailing number, it helps to examine the mechanics behind a typical tow truck’s capacity. Most standard tow trucks are rated to handle the weight of a single vehicle that falls within a broad range, commonly expressed in tons. In practical terms, a truck might be configured to manage anywhere from roughly 10 to 25 tons for a single towed vehicle, depending on the model and its construction. That rating is not an invitation to stack payloads or to combine forces in a single maneuver; it is a safety ceiling for one discrete vehicle. The moment you begin to think about towing a second vehicle concurrently, you quickly exceed the design intent of the chassis, the powertrain, the braking system, and the steering geometry. The risk to the towed car increases, the operator’s ability to manage load distribution diminishes, and the chance of uncontrolled swaying or loss of control rises sharply. This is not a theoretical constraint. It is a fundamental consequence of how the interactions between vehicle weight, hitch points, lift systems, and braking dynamics play out on real roads.

Yet, there are rare, highly controlled contexts in which a fleet might orchestrate multi-vehicle recoveries. In large-scale fleet operations, or during specialized urban or industrial recoveries, one tow truck can be part of a coordinated chain that involves multiple machines. In these cases, the process is less about hitching two vehicles to a single truck and more about staging a well-planned sequence, using winches, chains, and precisely calibrated control to pull, cradle, or winch one vehicle while another remains stationary or is carefully prepared for transfer. This is a far cry from conventional roadside towing and demands meticulous planning, sophisticated communication, and equipment that is explicitly designed for such complexity. Even then, what is truly happening is not a single tow truck hauling multiple cars down the road; it is a choreography of several machines each handling a single, carefully managed portion of the operation. The practical outcome, in terms of safety and roadworthiness, remains a one-vehicle-at-a-time scenario for each individual truck involved.

A deeper dive into the engineering behind these capabilities reveals why the one-vehicle-at-a-time model endures. The weight and size of the towed vehicle are the primary determinants of how much stress the tow truck can safely tolerate during acceleration, deceleration, and steering. A heavy truck, a large van, or a bulky SUV places a disproportionate load on the hitch and the platform, raising the risk that wheels could lift, the trailer brakes could overheat, or steering control could degrade under the pull. Even with sophisticated braking systems and hydraulic lift arrangements, the load distribution across the tow truck’s axles must stay within certified limits. Road conditions can magnify any marginal loading decision. A slick, downhill grade, a sharp turn, or a gusty crosswind all compound the difficulty of maintaining a steady, controlled recovery when the entire system is configured to handle a single vehicle. In rough terrain or poor weather, those risks multiply, making any attempt to tow additional vehicles simultaneously not just unsafe but largely impractical.

This is reflected in both practice and policy. The industry standard priorities—safety, precision, and damage prevention—drive crews toward single-vehicle recoveries as the default. When a larger capacity is discussed, it is usually in the context of a particular vehicle’s weight rating or in a specialized scenario where the operation is carefully controlled and segmented. Even in those exceptional cases, the emphasis remains on protecting the towed vehicle from further harm and on preserving the operator’s ability to manage the recovery with predictable, repeatable movements. The result is a simple, robust principle that governs most operations: one vehicle, one controlled sequence, one safe recovery.

Still, the field cannot escape the occasional memorandum of a broader capability. Some operators and designers have explored configurations such as flatbed systems with pivoting platforms or advanced stabilization features that can contribute to more complex recovery scenarios. In theoretical or highly engineered environments—often urban multivehicle recoveries or caviar-grade precision operations—the equipment may be tuned to accommodate careful, coordinated actions that involve multiple machines rather than a single, oversized payload. References to control algorithms and load-distribution strategies sometimes appear in industry discussions. They signal a move toward safer, more precise multi-step recoveries rather than a single vehicle pulling another two down the road. Yet these discussions are more about extending the role of tow trucks in special circumstances than about redefining what a tow truck is meant to do in ordinary roadside work.

In practice, the takeaway is straightforward: for the vast majority of calls, the tow truck will recover one vehicle and transport it to safety or to a storage facility. If the situation presents itself as a multi-vehicle operation, it is not because the tow truck is pulling more than one vehicle at once; it is because several trucks are working in concert as a system. The coordination requires clear communication channels, a shared plan, and equipment designed for the purpose. It is still a sequence: recover the disabled vehicle, secure it for transport, and move it to a repair site or a lot. The chain remains careful, deliberate, and conservative to prevent downstream damage to any of the vehicles involved or to the surrounding environment.

This conservative approach is not merely a technical preference. It aligns with legal and regulatory frameworks that guide tow operations. Local regulations, manufacturer limits, and industry best practices emphasize preventing accidents and minimizing damage. The safest outcomes tend to be those achieved by adherence to manufacturer specifications and adherence to a well-planned recovery plan. The result is a mobility ecosystem where tow trucks function as reliable, predictable tools that restore order after accidents, breakdowns, or impassable road conditions—one vehicle at a time, with the potential for broader, controlled coordination only when circumstances demand it and the risks are thoroughly mitigated.

For fleets confronting island challenges or other environments where space, terrain, and weather create unique constraints, the principle remains consistent. The focus is on preparedness and adaptability rather than acceleration to large payloads. A well-prepared crew will plan for a range of scenarios, including the possibility of using multiple units in a staged recovery. They will prioritize equipment suited to single-vehicle recovery, along with supplementary tools that support winching, stabilization, and safe transfer. In this sense, the island fleet narrative reinforces the same core lesson: capacity is about safe capacity, not maximum spectacle. The safest and most reliable answer to how many trucks can tow a vehicle is that, in routine conditions, one is the standard, while additional vehicles may enter the operation only as part of a carefully supervised, multi-machine process. This is the thread that connects everyday practice to exceptional operations, and it anchors the chapter in a clear, practical reality for operators and municipalities alike.

For readers seeking ongoing industry perspectives and case studies that explore the evolving dialogue around tow capacity and multi-vehicle recoveries, the Island Tow Truck blog offers a focused lens on the front-line realities and the strategic considerations that inform fleet decisions. The discussion there often centers on readiness, response times, and the practical limits of equipment in real-world conditions, rather than on theoretical maximums. It serves as a useful companion to this chapter, grounding the technical clarifications in field-tested experience. the Island Tow Truck blog

In sum, while the allure of multi-vehicle tows can be compelling in fiction or dramatic news segments, the practical, safe, and legally compliant operations that keep roads clear and vehicles undamaged rely on one vehicle at a time as the default. When a broader capability is necessary, it is not a matter of stacking cars on the back of a single machine; it is a matter of orchestrating a controlled sequence across a fleet, with safety and precision as the constant, guiding principles. The takeaway is not to underestimate the power of a tow truck, but to respect the discipline that makes it capable: professional training, respect for limits, and a careful approach that treats each recovered vehicle as a separate, important step toward restored mobility.

External resource for further context: https://www.walmart.com/ip/Pre-Owned-How-Many-Trucks-Can-a-Tow-Truck-Tow-Pictureback-Paperback-0679878106-9780679878100/348477245

Final thoughts

Understanding the multifaceted aspects of towing capacity is vital for those managing local automotive services. Whether you’re operating a fleet or running a repair shop, knowing how truck size, vehicle weight, road conditions, and regulations influence towing decisions can enhance efficiency and safety. By considering all these facets, you position your business for success in the dynamic environment of island transportation.